Two giant icebergs broke off Antarctica.

Here's what that means for the continent's health.Original article here.

Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier is one of the most

closely watched pieces of ice on Earth, and scientists

are warning about -signs of climate change. Feb. 19, 2020, 1:58 PM CST

By Tom Metcalfe

Twitter: Tom Metcalfe @globalbabel

Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier is one of the most closely watched pieces of ice on Earth.For

years, scientists have tracked as chunks of the glacier have broken

off, an awe-inspiring event known as “calving” that happens naturally.

But it’s happening more often at the Pine Island Glacier, also known as

PIG, and it’s got glaciologists worried that climate change is to blame.“The calving events at Pine Island Glacier are coming more frequently than they used to,” said glaciologist Adrian Luckman from Swansea University in the U.K. in an email.Glaciologists

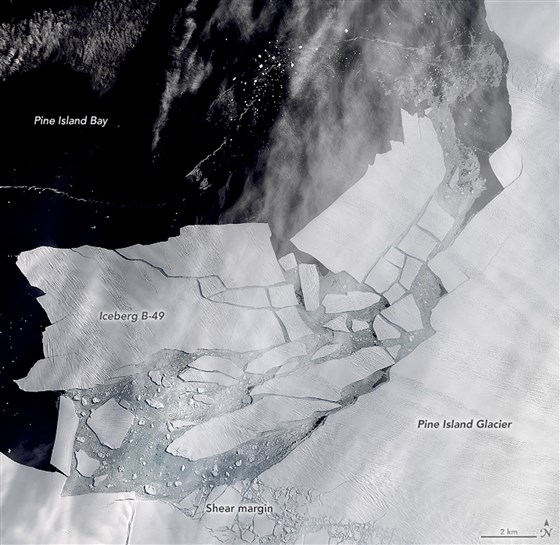

have raised alarm that a massive new iceberg, designated B-49, may be a

result of melting caused by relatively warm water eating away at the

ice that surrounds the frozen continent.B-49

is one of two large icebergs now floating away from Antarctica. It

broke away from PIG last week, while the other, a trillion-ton behemoth

dubbed A-68, broke away from the Larsen C Ice Shelf, on the east coast

of the Antarctic Peninsula, in 2017, scientists say.

Iceberg B-49 is about twice the size of Washington D.C.

But Iceberg A-68, unlike B-49, is probably not a result of a warming climate, said Luckman and other glaciologists.Iceberg

B-49 covers 40 square miles, while the many smaller icebergs that also

broke free on Feb. 9 cover another 80 square miles.An

international scientific team has just completed its first major field

season on the giant Thwaites Glacier, about 200 miles from Pine Island

Glacier, beside the Amundsen Sea in West Antarctica.They are trying to learn why glaciers in the region are melting.“This is a place where we know the ice shelves are thinning quite fast,” said glaciologist Helen Amanda Fricker from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. “It has been identified as an area that is changing rapidly.”Satellite

photographs show Thwaites Glacier and PIG have started flowing faster

in recent years, while their edges of floating ice have pulled back

toward the land.“The

increased frequency of calving seems to be related to the thinning of

the ice tongue,” Luckman said. “This is probably caused by the

incursion of warmer waters into the area, which may be related to

climate change.”Glaciers

in West Antarctica like the Thwaites and PIG worry scientists because

their melting could eventually expose inland glaciers and even more

ice, causing a drastic rise in sea levels.Some recent scientific models predict that Antarctica’s melting alone could cause sea levels to rise by almost 2 feet by 2100.Iceberg A-68, which covers more than 2,000 square miles, recently left Antarctica’s Weddell Sea, heading for the Southern Ocean.Several

research ships have since tried to study the pristine seabed it covered

for thousands of years, but the floating ice in the Weddell Sea has

been too heavy for them to get there.While

many icebergs break off from the normal processes of Antarctica’s

coastal glaciers flowing into the sea, Luckman said the changes in the

west of Antarctica appear to be caused by a warming climate.“Taken

as a whole, the generalized retreat of ice shelves along the Antarctic

Peninsula, and especially the thinning elsewhere such as at Thwaites

Glacier, shows clearly that climate change is causing accelerating mass

loss from Antarctica to the oceans,” he said. Tom Metcalfe

Tom Metcalfe writes about science and space for NBC News.Back to News